By Anastasia Bektimirova (Head of Science and Technology, The Entrepreneurs Network)

FOREWORD

Starting a company is one thing, turning it into a lasting success is an altogether harder task. Britain has become the most heavily incubated economy on a per-capita basis in the world, yet has a weakness in scaling up companies compared to the US and emerging competitors. We devote vast effort to helping new ventures take their first breath, but far less to ensuring they grow, export and endure.

The problem is not a lack of public money. Each year, local and central government backs hundreds of incubators, accelerators and regional growth hubs. What is missing is coherence. Too much funding is awarded on short grant cycles with scant evaluation, leading to a long tail of well-intentioned but under-performing programmes.

In a similar vein, only 2.5% of innovation investment is focused on established companies – the very firms whose productivity gains could lift wages and regional prosperity fastest. History tells me building on what you have is often easier, cheaper and quicker than starting afresh. By spreading our resources too thinly, we stunt the diversity of the entrepreneurial landscape and the pace of economic growth and regional development.

The provision of 38 regional growth hubs and business support programmes, delivered without a core national strategy and with constant short-term distraction based on short-term grants, is further exacerbating the challenges we face. The cost of this pattern is visible everywhere. Mentors drift away during grant gaps, alumni networks wither, founders lose faith when promised help disappears at a critical moment. In the West Midlands, for example, ten accelerator programmes have folded for every eight that remain active. Such volatility erodes entrepreneurs’ trust and wastes institutional knowledge.

We need a different approach. Public funds should not simply proliferate more of the same programmes but should concentrate on fewer, deeper, outcome-linked programmes – and only where it genuinely adds value rather than crowding out private capital. Long-term contracts, rigorous evaluation and a clear strategy would give the best operators room to prove and improve their impact, while freeing founders to focus on products and customers instead of chasing their next subsidised cohort.

This timely and insightful report not only starts the long overdue conversation we need to have about improving Britain’s landscape of incubators and accelerators, but also sets out the evidence and principles for reform. If we want the UK to generate the next generation of global businesses, we must act now and with purpose.

Steve Rigby is the Co-CEO of Rigby Group

Executive summary

Britain has no shortage of support initiatives for startups. It has one of the world’s most densely populated ecosystems of startup incubators and accelerators, which provide early-stage companies with mentorship, workspace, networking opportunities and other support. Indeed, as one expert has put it before, the United Kingdom is “the most heavily incubated economy per capita.” But this exciting diversity does not always translate into effectiveness. One incubator or accelerator may deliver strong outcomes for founders, while a similar programme next door yields far more limited impact. Over time, the terms accelerator and incubator have become popularised so broadly that virtually any business initiative focused on growth might claim the label. While flexibility is key for innovation, this ambiguity has led to a proliferation of programmes that share the same name but deliver highly variable results. This makes strategic government support challenging and confuses entrepreneurs seeking assistance.

This paper does not aim to map Britain’s network of incubators and accelerators – valuable work has already been done on this by others. Instead, we focus on the effectiveness of the incubator and accelerator ecosystem. Despite substantial public investment in this space, a coherent strategy to guide funding decisions and measure outcomes is lacking. Many programmes operate without clear definitions or metrics for success, or alignment with broader national priorities.

Drawing on interviews with industry experts with a track-record of creating and running incubator and accelerator programmes, founders who went through them, and desk research, this paper articulates opportunities to strengthen the impact of the UK’s incubator and accelerator ecosystem. We identify several principles that should guide public spending in this area to ensure that investment is targeted effectively, and to avoid a long tail of underperforming or misaligned programmes.

Our research cautions against startup programmes that call themselves accelerators but provide little more than basic workshops. We also uncover several areas that limit the current ecosystem’s impact. For example, many effective accelerators are working backwards from the investor portfolio they target, yet many UK accelerators lack a clear pathway to investment. At least partially for that reason, startups often hop through multiple programmes without gaining cumulative value, which suggests redundancy and poor specialisation in the support system. Short-term public funding cycles exacerbate these issues.

This paper articulates opportunities to improve the effectiveness of public resource allocation, with a view to increasing programme quality and accountability, and fostering greater coordination within the ecosystem. This includes establishing clear programme standards and classifications, shifting success measurements towards long-term entrepreneur development, and reforming funding models to reward outcomes that sustain and scale proven initiatives. With a more intentional approach to supporting incubators and accelerators, the UK can better leverage these programmes to drive innovation and entrepreneurship.

We recommend:

1. Establish standards and classification

OBJECTIVES → Create a national taxonomy and accreditation scheme for all support programmes, tying public funding eligibility to minimum standards.

KEY COMPONENTS

Develop a classification system spanning all programme types.

Set minimum standards on leadership experience, network-strength metrics, documented methodologies, and outcome-tracking commitments.

Define outcome metrics using both leading indicators and lagging results.

Launch certification and digital badges for accredited programmes.

2. Reform impact measurement

OBJECTIVES → Adopt a dual-track assessment that captures both company performance and entrepreneur’s development.

KEY COMPONENTS

Shift tracking focus from companies only to founder-centred metrics following talent across the ecosystem.

Issue founder-owned digital badges mapped to a shared competency framework modelled on EU EntreComp.

Prevent double-counting of company outcomes.

Apply evaluation with control groups/matched comparisons and ring-fence a share of contracts for independent studies to incentivise robust impact measurement.

3. Sustainable funding models

OBJECTIVES → Replace short-term grants with 3-5 year outcome-linked contracts plus rolling reviews and bridging finance.

KEY COMPONENTS

Provide baseline funding for 3-5 years through multi-annual budgets (carry-over permitted).

Run rolling annual reviews unlocking next funding phases when leading-indicator milestones are met.

Offer bridging finance to avoid gaps during re-competition.

Award bonuses to programmes that crowd-in private capital while sunsetting chronically under-performing ones.

4. Market-driven quality improvement

OBJECTIVES → Introduce demand-led funding vouchers redeemable with accredited providers.

KEY COMPONENTS

Pilot a voucher scheme allocating them competitively.

Split voucher allocation into cluster-aligned (regional/sectoral) and national competitive routes.

Maintain a registry of accredited providers meeting the minimum standards.

Track voucher redemptions and outcomes.

Introduction

Britain has no shortage of support initiatives for startups. More than 400 incubators and 300 accelerators were reported in the country in 2022, double the number from five years earlier. According to recent Beauhurst data used as a basis for the present analysis, the UK now hosts over 500 accelerator programmes.

This rapid growth reflects that structured support is a highly demanded component in the journeys of early-stage companies. Beauhurst estimates that nearly 80% of UK startups that join accelerators do so at the seed stage of development.

Figure 1: Company stage at the start of accelerator attendance

Source: Beauhurst data (2025).

These programmes represent substantial investment. Since 2016, around £219 million has been invested in accelerator programmes through Innovate UK alone. [1] While many have valuable impact, questions nonetheless persist about effectiveness, strategic alignment, and return on investment. While the quantity of programmes certainly has merits, this almost inevitably means that the landscape is also characterised by variation in quality, approach, and effectiveness.

In the absence of clear standards or shared definitions, entrepreneurs can struggle to navigate the support ecosystem and identify which programme will genuinely help their venture. A disconnect between expectation and reality often reduces the value of these initiatives for founders and leads some to bounce between multiple programmes seeking the right support. At the same time, public and private funders lack reliable criteria to decide which programmes to back, making it hard to ensure money flows to the most effective ones.

It is also clear that current programmes do not serve all types of entrepreneurs equally. High-growth technology startups might find ample accelerator options, but founders pursuing alternative paths can fall through the cracks. For example, experts noted a dearth of support for what might be termed “small giants” – companies aiming for sustainable growth rather than rapid scaling – as well as for creative industry ventures and place-based businesses deeply tied to local communities. These gaps limit the diversity of the UK’s entrepreneurial landscape and may constrain broader economic growth and regional development. In other cases, support exists but is misaligned: for instance, trying to shoehorn a biotech spinout or social enterprise into a generic accelerator curriculum may do more harm than good.

Against this backdrop, this paper, combining expert interviews and desk research, examines where and how improvements can be made to boost overall outcomes.

Definitions

The terms for different support models are frequently misused, creating confusion for entrepreneurs, investors, and policymakers.

This paper distinguishes between:

Incubators: Programmes that typically provide physical space, basic business support services, and networking opportunities over an extended period. They focus on early-stage idea development and venture formation, usually without taking equity.

Accelerators: Time-limited programmes, often cohort-based, that should specifically prepare companies for investment and market traction. Accelerators provide intensive support to make startups investment-ready and connect them with relevant investors.

Venture builders/studios: Organisations that go a step earlier in the company creation cycle by actively co-creating startups (bringing together ideas, founding teams, and capital in-house).

Business support programmes: General entrepreneurship education and advice services that may use accelerator terminology but lack the specific focus on rapid growth and investment readiness that defines true accelerators.

These distinctions matter because the appropriate structure, metrics, and funding models will differ significantly between these programme types. Despite these differences, in practice the boundaries often blur. Some incubators run accelerator-style training modules, some accelerators also offer physical co-working space like incubators. New hybrid models like venture studios are growing too, which ideate and launch companies from scratch, providing the services of an incubator but also acting as a co-founder with a stake in the venture. This report treats incubators and accelerators broadly as part of one continuum of startup support, but where relevant we distinguish among different models, as their needs and impacts can differ.

Funding mechanisms and sustainability models

The funding arrangements for incubators and accelerators are similarly diverse, including:

Public sector-funded programmes: Many are supported by government grants or subsidies through national public funding bodies, such as Innovate UK, local and regional authorities, or universities (often through Higher Education Innovation Funding).

Privately funded and corporate programmes: A number of accelerators are run by venture capital firms (seeking equity in promising startups as their return), by large corporations as part of their innovation and scouting efforts, or by property such as science parks. Examples include corporate accelerators run by banks or accountancy firms, or industry-specific accelerators backed by companies looking for strategic investments, talent acquisition, or access to new ventures as future customers. These tend to be financially sustained by the parent firm’s budget, by taking equity stakes, or rental income.

Hybrid models: Some initiatives blend public and private funding. For example, a local accelerator might receive a government grant to cover operational costs, while also securing sponsorship from a corporation and equity investment from investors for startups.

Public funding plays a significant role in this ecosystem. For example, since 2016, around £219 million has been invested in accelerator programmes through Innovate UK alone. [1] Successive governments have launched schemes to increase the availability of startup support, seeing it as an investment in innovation and entrepreneurship. Their support comes through multiple channels, including:

The UK Shared Prosperity Fund (formerly the European Regional Development Fund);

Innovate UK grants and competitions;

The Higher Education Innovation Funding (HEIF);

Local Growth Funds through Local Enterprise Partnerships;

The British Business Bank’s involvement in venture funding.

Despite such investment, there is limited coordination of how these funds are allocated and patchy strategic oversight of what outcomes they achieve and how these programmes fit into the wider ecosystem of advisers, funders and other parts of the entrepreneurial value chain.

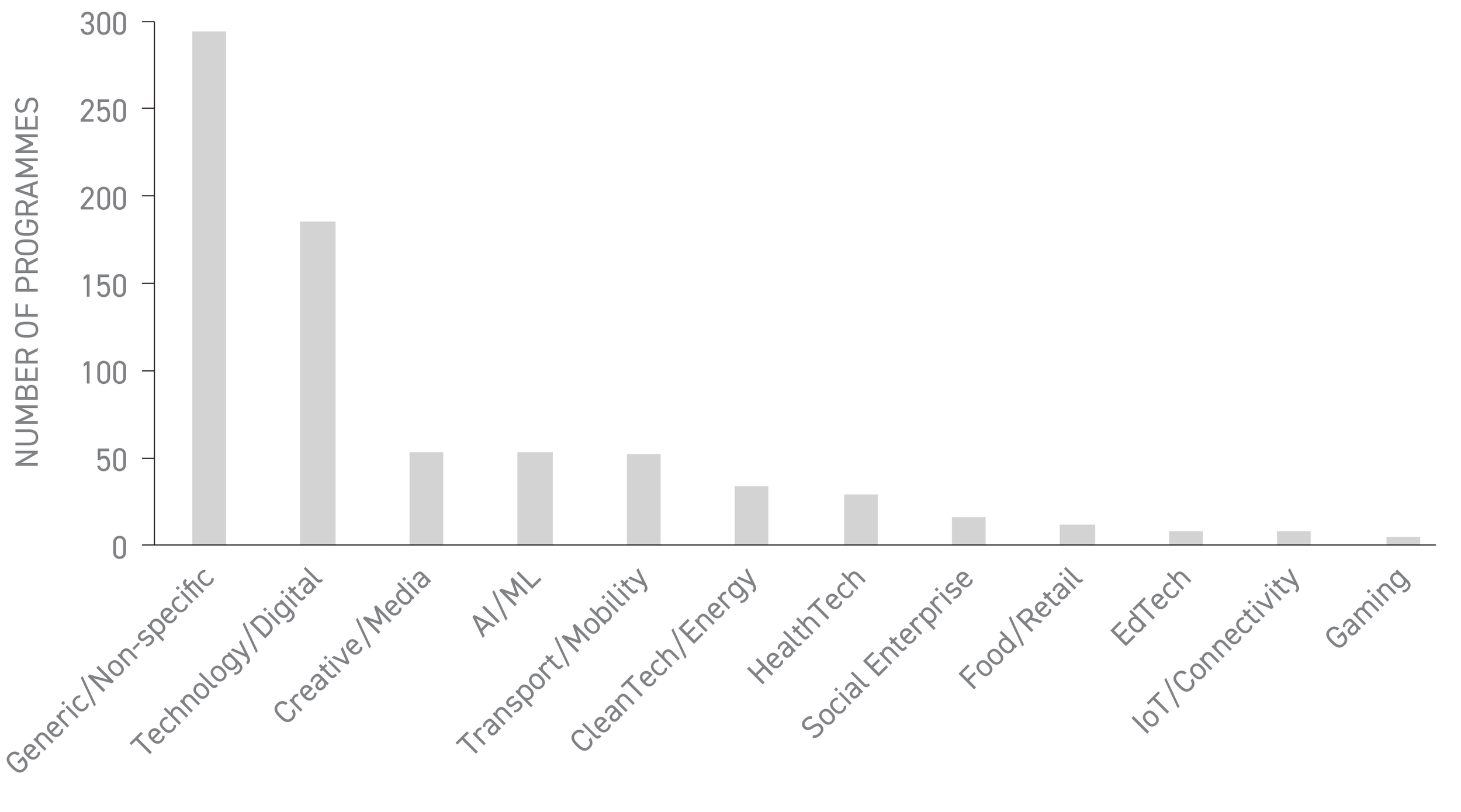

Sectoral distribution

Britain’s accelerator and incubator ecosystem includes both generalist programmes and those specialising in specific sectors. Among specialised accelerators, technology-focused programmes dominate, but there are gaps in support for certain sectors, particularly:

Deep tech requiring specialised facilities and longer development timelines;

Traditional manufacturing and industrial technologies;

Social enterprises and non-VC-backed business models.

Figure 2: Sector focus of accelerator programmes

Source: Beauhurst data, The Entrepreneurs Network analysis (2025).

Regional distribution

Regional distribution of accelerators largely mirrors the UK’s broader economic geography, with concentration in London and the South East, and strong presence in urban centres. This pattern reinforces existing regional disparities and raises questions about whether public funding should address these imbalances or build on existing strengths.

Figure 3: Number of accelerator programmes, by region

Source: Beauhurst data, The Entrepreneurs Network analysis (2025).

London’s lead is clear. Over 300 programmes – nearly three fifths of all accelerators – operate in the capital. The next‑largest region, Scotland, hosts just 36, followed by the East of England with 33, while every other region sits below 30. After London, there is a steep drop‑off, creating a long tail of lightly served areas.

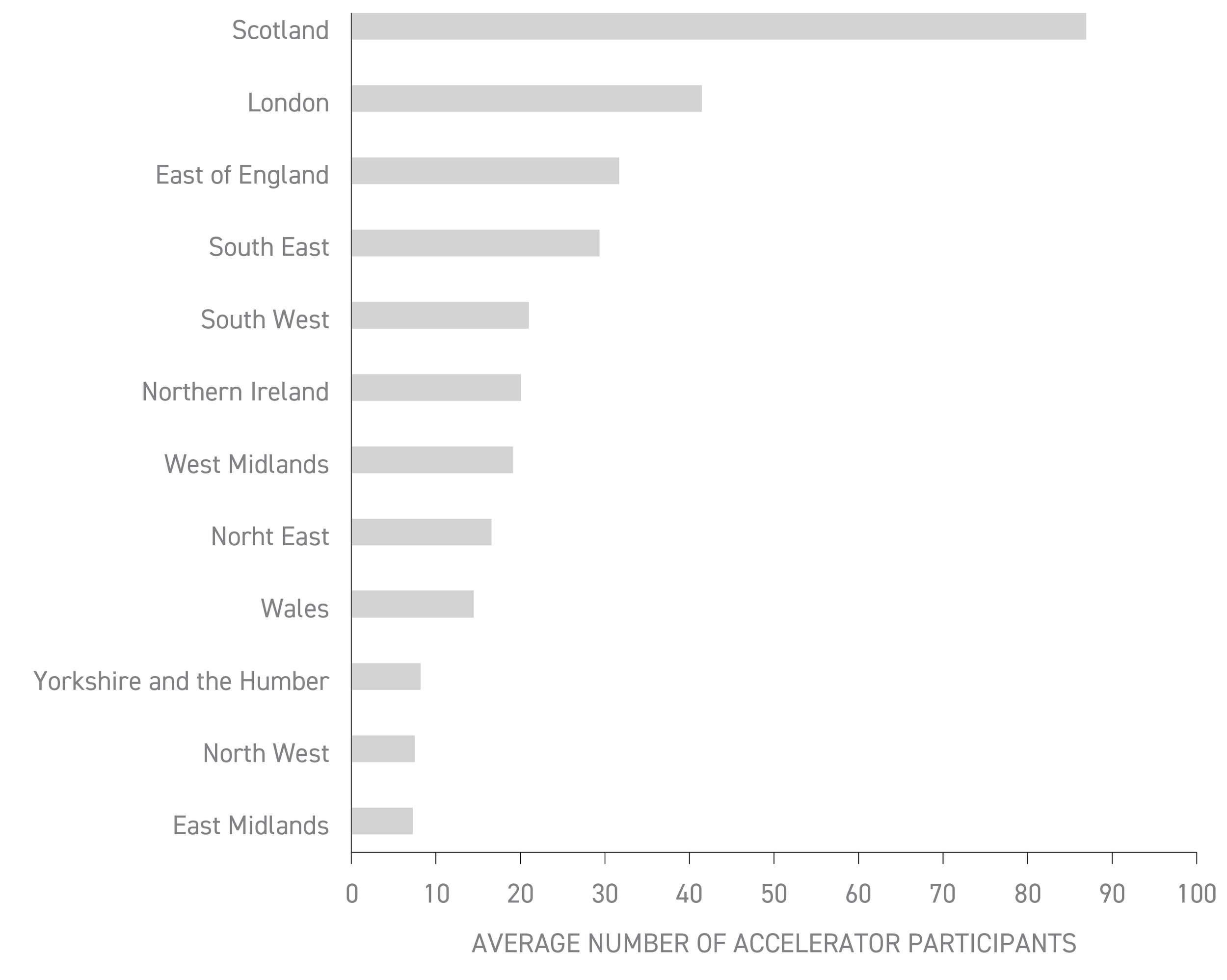

Figure 4: Average number of participants per accelerator programme, by region

Source: Beauhurst data, The Entrepreneurs Network analysis (2025).

Accelerator capacity is far from uniform across the country. London leads on absolute scale, but the average number of attendees, around 40 startups, reflects sheer volume rather than congestion – programmes are plentiful as well as busy.

Scotland is the outlier. Its combination of high number of attendees and scarce provision suggests unmet demand. Large, oversubscribed cohorts can dilute attention, while ultra‑small ones struggle to generate network effects. The Scotland example highlights a mismatch: founders flock to the few credible programmes available, but capacity hasn’t kept pace with regional talent growth. This could indicate a potential priority for future public support: target capacity expansion where founder demand already exceeds supply.

One in three programmes branded as accelerators has already ceased operations. Programme sustainability varies sharply by region (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Operational status of accelerator programmes, nationwide and by region (n = 549)

Source: Beauhurst data, The Entrepreneurs Network analysis (2025).

Nationally, only 57% of listed incubators/accelerators are active (‘Green’) while 33% have closed (‘Red’) and 10% are in limbo (‘Amber’). [2] London hosts 59% of all programmes, but their survival rate (60% active) mirrors the national average. Some regions show even higher attrition:

In the West Midlands, for every eight active programmes there are ten that have already shut down;

The East of England sustains a healthier ecosystem: nearly two‑thirds (58%) of programmes remain active and only six are inactive.

Addressing regional disparities is not simply a matter of setting up more accelerators outside London. It requires tailoring support to local strengths, local economic development strategies, and linking regions to wider networks. It also requires efforts to develop regional ecosystems through initiatives such as such as startup meet-ups and building connectivity between existing initiatives and universities, incubators, accelerators, alongside attracting investors to the region. The current picture is one of concentration and fragmentation: a few well-connected hubs and many other areas with patchy support. Bridging this gap will require playing to each region’s strengths and network-building to ensure no founder is an island.

WHERE AND HOW SHOULD GOVERNMENT INTERVENE?

The startup support ecosystem does not always function as an efficient market. There are market failures and gaps where relying on private initiatives alone leaves blind spots. Early-stage ventures often create broader economic and social benefits (knowledge spillovers, job creation, regional growth) that private investors may overlook as the benefits of early-stage support only materialises in the much longer term, leading to under-investment in incubators and accelerators as quasi-public goods. At the same time, substantial public funds are already flowing into these programmes without a coherent overarching approach. The following are the priorities the public sector approach could follow:

PRINCIPLE 1: OUTCOME-BASED, NOT ACTIVITY-BASED, FUNDING

Public funds should not simply proliferate more programmes, but reward those that deliver positive, measurable outcomes. This stands in contrast to funding based on short-term metrics like number of entrepreneurs trained or events held. Outcome-linked funding implies a longer-term commitment, as many benefits only materialise after several years. Government should fund fewer, better programmes with meaningful impact, and structure that funding to focus attention on delivering real entrepreneurial success stories.

PRINCIPLE 2: THE MECHANICS OF PUBLIC FINANCE SHOULDN’T SABOTAGE GOOD PROGRAMME DESIGN

Public grants should span multi-year periods with staged milestones, rather than one-off annual grants that encourage a quick hit of activity. Government should try and uncouple timelines for funding programmes from budget cycles. Programme operators told us that too often, funding decisions are confirmed late in the fiscal year yet still require spending by the end of the financial year, compressing delivery and undermining quality. Ring-fenced, multi-year allocations that can roll forward across financial years would free operators to plan cohorts, recruit staff and conduct outreach at the right pace.

PRINCIPLE 3: LEVERAGE, NOT REPLACE, PRIVATE CAPITAL

Public investment in incubators and accelerators should amplify rather than displace private capital, but that does not mean withdrawing public money wherever the market shows interest. Private-sector models typically recover costs by taking equity or charging fees. If government funding vanished from well-served hubs, entry would become exclusive, reinforcing the advantages of founders who can afford to pay. The aim, therefore, is not to substitute public with private finance, but to blend the two so that every taxpayer pound unlocks additional resources while programmes remain accessible to diverse entrepreneurs.

Accelerators are rarely profitable businesses in their own right: they create value indirectly for landlords (by activating workspace), investors (by generating deal flow) and corporates (by providing talent and innovation pipelines). Where those actors are already active and willing to pay, government can scale back to a lighter-touch role. For example, offering bursaries that cover a founder’s fees at a privately run accelerator, or underwriting scholarships for under-represented entrepreneurs. In regions or sectors where the commercial ecosystem is thin, public money should take a heavier share, underwriting operating costs until a critical mass of private partners emerges.

Where possible, the public sector should partner with private sector organisations to deliver the programmes in such a way that over time, the partners are motivated to continue them without the public funding.

PRINCIPLE 4: RIGOROUS EVALUATION AND SUNSETTING OF PUBLICLY FUNDED PROGRAMMES

At present, many programmes operate with public money but without rigorous checks on whether they are delivering value for money or just look busy. Programmes should be held to clear governance and standards, with continued public support contingent on meeting agreed milestones. For example, this could operate in the following manner:

An initial multi-year contract would be awarded only if the proposal targets a genuine market gap, with optional extension years written in but never automatic. Progress would be judged against a score-card that blends near-term signals, such as quality of investor introductions, participant satisfaction and prototypes delivered, with a light-touch, long-term tracker of company or founder growth and partnerships. If early evidence suggests a programme is drifting, the default response would be a jointly agreed improvement plan rather than a claw-back of funds. Only if performance still lags after remediation would the next funding tranche be withheld and the programme allowed to sunset. Programmes that deliver or outperform would activate extensions.

PRINCIPLE 5: SUPPORT THE TOP OF THE PYRAMID

International evidence shows that a handful of world-class programmes, such as Y Combinator, IndieBio, and Creative Destruction Lab, or startup campuses such as Station F in France, act as powerful signal-boosters for an entire ecosystem: they attract global investors, anchor local talent and push up standards for every programme beneath them. The UK lacks a comparable, globally-recognised elite-tier accelerator focused on research commercialisation. Public support should therefore be weighted towards creating and scaling a small number of R&D-intensive, internationally benchmarked programmes with the specialist resources and governance needed to match the best in the US and Europe. Doing so would lift the whole distribution of programme quality.

strategic fit

There is a proliferation of a long tail of programmes that don’t necessarily deliver on the perceived promise of the incubator or accelerator label. For example, the original concept of accelerators like Y Combinator was designed to work backward from the portfolio requirements of venture capital firms, providing a clear pathway to investment. But many programmes lack this strategic focus, instead offering generic support without a defined investment pathway. This misalignment in expectations and reality risks creating inefficiency in resource allocation and missed opportunities for founders.

Figure 6: Most common features advertised by UK accelerators, based on 665 accelerators with known features

Source: Beauhurst (2025).

A majority programme lists mentoring (83%) and most offer some form of expert or business network access. But access to the investor network is explicitly offered by less than half (48%).

More tangible, capital‑intensive perks are rare. For example, 29% of programmes provide direct financial investment, 19% offer dedicated office space, and fewer than one in five supply technical facilities, stipends or professional services such as legal or accounting support.

This confirms the insights from expert interviews that many accelerators prioritise workshops and advice over the hard resources and investor connections needed to reach scale. The mismatch is most visible in sectors requiring expensive prototyping or deep regulatory preparation, where access to laboratories or specialist advisers is essential yet almost entirely absent from the typical benefit mix. Programmes should move beyond ‘mentoring and workshops’ and build differentiated offers, aligned to address the concrete gaps founders face.

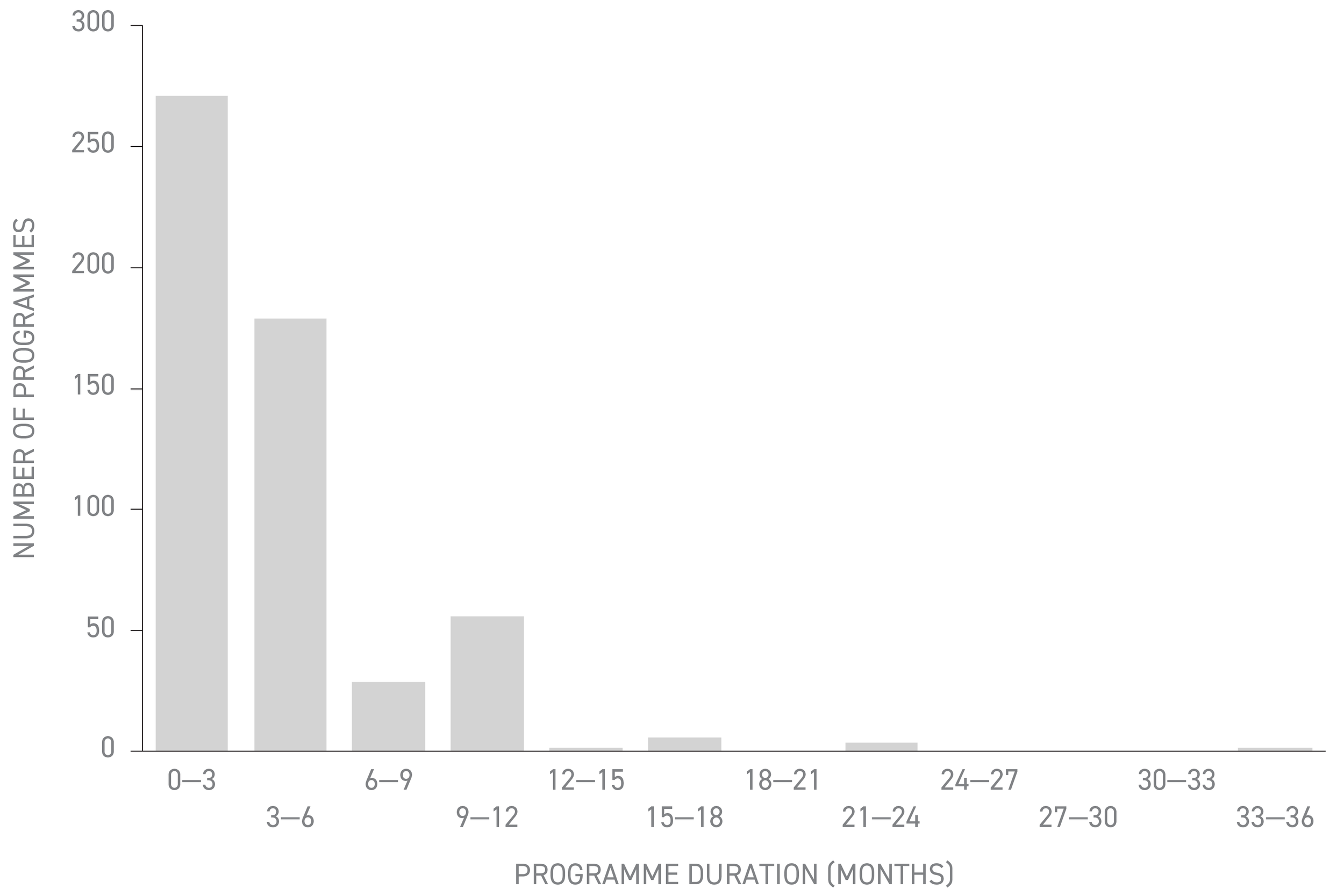

Figure 7: Distribution of UK incubator/accelerator programme duration

Source: Beauhurst data, The Entrepreneurs Network analysis (2025).

Another concern is programme duration. Figure 7 shows how skewed UK accelerators are towards short cycles. Around 80% offer cohorts of six months or less, with the single largest cluster (271 programmes) in the 0-3‑month band. Only 12% run beyond nine months, and programmes longer than a year are vanishingly rare (2.5%).

For many software or B2B SaaS startups, a shorter timeline can work. Yet founders in deep tech, life sciences, manufacturing or highly regulated markets may need a longer period of structured support to reach investability. This pattern suggests that accelerators optimise for quick outputs, while innovators with longer gestation periods are left to piece together ad hoc support.

In principle, a dominance of short programmes would be fine if they sat inside a coordinated ladder of support: pre-accelerator discovery labs feeding into short accelerators, then into longer follow-on scale programmes – all clearly sign-posted. In practice, the collection of programmes has largely evolved and is marketed in isolation, producing both overlaps and gaps. A stand-alone three-month course rarely changes founder trajectories if it ends with no onward route. Likewise, survival stipends, workspace provision, and deep mentoring each operate on different timescales, so compressing them all into a generic, short-format bootcamp dilutes impact. The priority should be not to abolish short cohorts but to embed them in an intentionally sequenced ecosystem and to ensure that sectors requiring longer development cycles have access to programmes designed on a matching timetable.

Alignment with founder and market needs

Many accelerators fail to address the needs of founders they aim to support. It is not uncommon for self-described ‘accelerators’ to operate more as general business support initiatives without the methods and resources that define genuine accelerators. This terminology problem can create confusion for founders attempting to identify the support they need. Multiple experts we spoke to during this research described encountering startups that had been through three or four different programmes without gaining cumulative value, which signals serious inefficiency in the support ecosystem.

This ambiguity creates three key issues:

Time horizon mismatch: Programmes designed for quick outcomes when participants need longer-term support, reflecting actual development cycles. A three-month sprint may be perfect for a software venture but insufficient for life-science founders who require lab access and regulatory sign-off that can take a year or longer;

Training over connections: Focus on educational content when participants most value introductions to customers, investors, collaborators, and relationships built within a cohort;

Generic approaches: One-size-fits-all methods that fail to address sector-specific knowledge, including on-site facilities access, or specialised networks essential for founders’ success. When an early-stage business is put through a rigid process that doesn’t match their needs, it can set them back more than it can help.

Without clear definitions and benchmarks, entrepreneurs struggle to navigate the support landscape and identify which programmes will genuinely advance their ventures. A disconnect between expectations and reality reduces the value of programmes for founders and contributes to them cycling through multiple ones seeking the support they need. At the same time, public and private funders lack reliable criteria for investment decisions.

Addressing these issues requires raising the bar for what accelerators offer and ensuring better specialisation. Not every programme should try to serve every type of startup. But this does not mean carving the ecosystem into vertical silos. Instead, every programme should be encouraged to have a clearly defined niche – a sector, stage or founder archetype – and the depth of expertise to serve it. Where clusters already have critical mass, that niche can be sector-specific: a climate-tech accelerator offering lab access and regulatory mentorship. Elsewhere, specialisation can be delivered through hybrid models. For example, local partners handle workspace and day-to-day coaching. What matters is not that every accelerator becomes narrower, but that no programme pretends it can meet all needs. This way, outcome-based support would reward those that match their promise with real value.

RECOMMENDATION 1:

ESTABLISH A CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM FOR STARTUP SUPPORT PROGRAMMES AND USE IT AS BASIC CRITERIA IN PUBLIC FUNDING DECISIONS

1. Develop a classification system recognising the full range of support models now operating in the UK and matching terminology with clear criteria. It could resemble:

2. Tie minimum standards to it, covering key components such as:

Leadership experience requirements (e.g. founding or investment track record);

Quantifiable network strength metrics (e.g. active investor relationships);

Documented methodologies appropriate to venture stage and sector;

Commitment to robust outcome tracking and reporting – appropriate to the programme’s stage and accommodating new entrants.

These standards should be applied in a way that does not exclude new providers – for instance, a programme with no alumni yet could qualify by outlining a rigorous outcome-measurement plan, even if it lacks past outcome data.

3. Implement outcome metrics that mix leading and lagging indicators.

Impact may take years to materialise, so every programme should track a small set of leading signals (e.g. number of qualified customer introductions) alongside lagging results (e.g. revenue, jobs, follow-on capital three years out).

Each programme’s results should be reported in the context of a clear logic model (Theory of Change [3]), linking its inputs and activities to short-term outputs, and ultimately to long-term outcomes and impacts. This alignment would make evaluations more comparable and meaningful.

4. Introduce certification and visibility measures to ensure entrepreneurs can make informed decisions, such as a digital badge system for certified programmes to display on websites and marketing materials.

This would enable entrepreneurs to make informed choices, help funders allocate resources more effectively, and create healthy market competition based on quality.

Measuring impact on both companies and founders

The preference for delivering quick wins for the programme – often defined in numbers of graduating startups or funding secured – is not necessarily also a win for the entrepreneur.

This is partially tied to how impact is measured and reported, as inappropriate metrics can create perverse incentives. Multiple experts described a disconnect between the commonly used metrics (focused on companies and immediate outputs) and long-term value creation (focused on people and their entrepreneurial journey). For example, an entrepreneurial journey of a founder supported today can ultimately result in the creation of a successful company years and multiple ventures later. This way, impact is a patient investment in people, rather than a snapshot of immediate business outcomes. From this perspective, an accelerator’s impact might be better reflected in the entrepreneur’s personal development, such as skills, mindset, network, rather than the immediate fate of their startup, as well as the network of founders, mentors and investors that compounds over time.

Against this backdrop, there are several limitations of standard impact measurement practices:

The attribution fallacy: With startups participating in multiple programmes, current attribution methods can lead to misleading conclusions about impact. Impact is also often exaggerated through overlapping claims – when a startup raises funds, multiple accelerators may simultaneously claim credit, leading to artificially inflated ecosystem figures. This undermines the accuracy and credibility of reporting;

The accelerator-hopping: If entrepreneurs attend multiple programmes without clear progress, it suggests that programme metrics fail to capture or incentivise genuine learning and development;

Counterfactual blind spot: Success rates matter if they exceed those of comparable companies that never joined the programme. Simple matched-group comparisons, similar to the evaluation of the Growth Vouchers Programme, should be standard, so accelerators claim impact only when they outperform the baseline;

The ‘first bet’ effect: One expert described programmes that appeared to fail by conventional metrics, yet provided foundational support and confidence that enabled participants to thrive in future ventures – an impact often overlooked in evaluations;

Long-term lag and attribution decay: Many accelerator benefits only emerge years later, making it hard to attribute success to any single programme. As time passes, entrepreneurs and analysts may forget or undervalue an accelerator’s contribution – an amnesic attribution effect that current short-term metrics miss;

One size doesn’t fit all: Application of uniform metrics across diverse types of accelerators is problematic. For example, a programme focused on social science research commercialisation can’t be judged by the same metrics as the one focused on deep tech ventures – the number of graduating companies and the scale of funding they raise don’t always translate across different contexts.

There is a tendency to measure what is easy rather than what is meaningful. For example, counting the number of startups served or events held (activity-based metrics) is straightforward. But to align metrics with impact, we need to shift the measurement from companies to people. This could involve tracking founders over a longer period beyond the programme: Did they start new ventures? Did they become successful innovators or leaders in other organisations? Are they applying the skills learned to create value?

RECOMMENDATION 2:

RETHINK IMPACT MEASUREMENT BY SHIFTING FROM COMPANY TRACKING TO A DUAL-TRACK EVIDENCE MODEL

Existing data platforms, such as Beauhurst, Dealroom, and The Data City, already track company outcomes through revenue, new jobs created and investment. While these indicators are valuable, impact assessment should be extended to also include founder-focused measurement, including through combining it with direct founder input on their progress. Crucially, when measuring and reporting accelerator impact, it’s important to ensure that one startup’s or entrepreneur’s performance is counted once, not multiple times.

Layer in founder-centred metrics to track entrepreneurial talent through innovation ecosystems: Rather than solely measuring company outcomes, evaluation should focus on the network effects and human capital development that accelerators generate. This requires developing privacy-compliant methodologies to track individuals' entrepreneurial journeys across multiple ventures and roles, using publicly available data sources as a foundation. For example, North Data uses Companies House director records to identify and group individuals to track what they are adding to the ecosystem. Similar registries could be leveraged to follow individuals’ roles in multiple ventures. For example, whether an accelerator alumnus later becomes a serial CTO;

Accelerator impact metrics should include founder progression: Programmes can incentivise entrepreneurs to share data on their own development (skills gained, networks built, follow‑on projects). This can be pursued through a combination of the following:

Accelerators might issue digital badges for achieved competencies (e.g. in leadership or technology skills), mapped to a common competency scheme (for example, modelled the EU’s EntreComp levels). Programmes would supply the verification metadata. Over time, the aggregate distribution of badges would reveal how many founders reached, for instance, ‘level-3 opportunity recognition’, without government holding a dossier on every individual;

At the local government level, the Cities of Learning digital badge system offers a template for how public bodies can support a decentralised skills record. Learners earn badges from various workshops and courses, collected in a unified skills wallet. Applying this to startups, a founder in London might earn a ‘Prototype Builder’ badge from a university accelerator and a ‘Pitch Expert’ badge from a startup bootcamp, each issued independently but all visible on the founder’s profile – established on an optional, opt-in basis;

In Europe, the open badging movement has influenced entrepreneurship support programmes. For example, in addition to the TU Dublin Digital Badges, the EU Erasmus+ programme has funded projects using gamified badges for young entrepreneurs, such as awarding a ‘Junior Startup Scout’ badge for completing entrepreneurship workshops;

Founder‑owned data records: To minimise reporting burdens and respect privacy, founders should be given control of their data. Entrepreneurs could maintain personal portfolios where they log mentoring, coaching and learning experiences. This founder‑driven data collection would ensure that qualitative support inputs are captured naturally. It would complement programme data and avoid privacy pitfalls. A founder‑owned record would turn each entrepreneur into an active reporter of their own progress;

Longitudinal tracking: Collecting long-term data on founders and startups is essential. Sustained follow‑up – through alumni surveys, periodic data pulls from registries, and integration with founders’ own profiles – is needed to see how early support translates into later success. Without such continuous tracking, evaluation relies on proxies that may miss true impact. In practice, this requires ongoing effort from both programmes and entrepreneurs, but it is critical for a robust evidence base on what works;

To incentivise reporting, it could be linked to professional development or academic accreditation. For example, collaboration with universities could offer founders certificates or credits to use on select courses, contingent on tracking their venture’s outcomes;

Data governance considerations: Where public records end, more sensitive data (e.g. LinkedIn employment histories) must rely on explicit participant consent and GDPR-compliant APIs – not covert scraping;

Invest in robust evaluation methodology: Public contracts should ring-fence a fixed share for evaluation that uses control groups or matched comparisons. Annual surveys (e.g. mentor ratings, investor NPS, cohort peer scores) would provide early feedback, while longitudinal panels would follow a sample of founders for five years to capture spillovers and second-time successes.

The evaluation system should also employ control groups, comparing accelerator participants against matched cohorts of similar companies (by sector, stage, and size) that did not receive support, to establish additionality rather than selection effects.

These insights about entrepreneurial capabilities would enrich the impact data that the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology already collects about the accelerator programmes it funds. Entrepreneur-first lens would capture benefits traditional programme metrics ignore: serial-entrepreneur pipelines, mentor spinouts, cross-cohort collaborations and alumni who later reinvest locally.

The impact measurement system could be further enhanced with sector-appropriate differentiation, informing how accelerators are assessed.

Start-stop funding

Organisations with longer-term investment horizons outperform others on financial metrics and non-financial outcomes like job creation and sustainability. The same logic applies to investment in innovation spaces, such as incubators and accelerators.

While not all funding should come from the public sector – accelerators and incubators should proactively seek ways to sustain themselves – by default, these are not profit-making programmes unless they take equity or establish complementary revenue streams. For example, Sheffield Technology Parks has a financially sustainable model, because it developed a structure with office space that generates revenue, which is then reinvested into the coworking space and entrepreneurship support thanks to its not-for-profit company status and a mission statement focussed on economic development. Bruntwood SciTech are for-profit but have a similar way of using income from office rental to subsidise incubation space and some programmatic support.

Multiple experts pointed out that the way public funding models are set up can inadvertently disrupt ecosystem development by breaking critical momentum and relationships. For example, an expert involved in running the UK Space Agency accelerator said that during the course of its operation, there was a 15-month pilot followed by a six-month break followed by more funding. The break meant that the momentum that was built up in the pilot, including all of the contacts and entrepreneurs that the accelerator got, and the growth of an ecosystem around the programme, stopped.

The problem is compounded by the project-dependent nature of funding, where each new initiative requires new application processes, reporting systems and focus alignment. For example, 8-12 month projects or programmes that don’t have follow-on support, struggle to build a community – a key value accelerator programmes bring.

This stop-start funding pattern creates a number of problems, including:

Network degradation: Carefully cultivated networks decay during funding gaps, forcing programmes and ecosystems to rebuild rather than expand relationships;

Talent flight: Expert staff leave during uncertain periods, taking institutional knowledge and relationships with them;

Broken trust with entrepreneurs: Startups that depend on promised support find programmes suddenly unavailable at critical points in business development;

Impact on applicant quality: Stable, longer-running programmes tend to attract stronger startups, as a consistent track record builds trust and reputation. In contrast, stop-start programmes struggle to recruit the best entrepreneurs. Founders may be wary of support that might vanish mid-way. Over time, continuous funding improves the calibre of applications, improving programme outcomes;

Loss of community: Discontinuity makes it particularly hard to build programme continuity, shared experience, and community;

Focus diversion: With each new funding source, even if a new round from the same public funder, an accelerator might have to tweak its focus to fit the needs of the sponsor, potentially diluting the original mission and offer;

Resource inefficiency: Short-term grants force programmes to spend excessive time and money on repeated applications, setup, and shutdown. This start-stop process wastes funds on bureaucracy and overheads (each new initiative requiring new bids, reports, etc.) instead of delivering support, making the funding less cost-effective.

RECOMMENDATION 3:

SHIFT TO A LONGER-TERM, OUTCOME-LINKED PUBLIC FUNDING MODEL FOR STARTUP SUPPORT PROGRAMMES

Public funding for incubators and accelerators tends to be allocated upfront, based on projected activity rather than demonstrated impact. This encourages a proliferation of programmes focused on quantity over quality, with little incentive to support ventures through to meaningful outcomes (e.g. scaling up, significant job creation, or retention in the region). By moving to multi-year commitments, programmes would avoid wasted restart costs and can build a solid reputation that attracts the most promising startups.

To address this, a fixed-term, project-based funding approach could be replaced with longer-term funding guarantees tied to outcomes:

Replace annual, project-style grants with multi-year, outcome-linked service contracts:

Baseline funding for three to five years underpinned by multi-annual budgets and permitted carry-over;

Rolling annual reviews unlock the next phase of funding against leading-indicator milestones. Underperformance would trigger an improvement plan rather than instant termination;

Bridging finance (a modest standby facility) would prevent damaging gaps while re-competition or improvement plans run;

Selective bonuses would reward programmes that demonstrably crowd-in private capital. Metrics would be chosen for relevance, such as export revenue for soft-landing hubs, clinical-trial progress for med-tech, rather than one-size-fits-all ‘jobs in region’ approach;

Sunsetting clauses would be introduced so that the programmes that repeatedly fail to meet milestones are defunded, freeing resources for more effective initiatives.

This dynamic, milestone-driven model would ensure that resources flow rapidly to the most effective programmes at the moments when additional support can unlock further growth, rather than stalling promising progress due to rigid, pre-set funding limits. In this way, public investment adapts to real-world outcomes, maximising the returns.

Driving quality through market dynamics

The current model is largely supply-driven: support providers are funded upfront regardless of performance, resulting in a lack of market orientation and weak accountability for outcomes. As we discussed in this paper, there is little strategic targeting too, as resources are not consistently directed at priority sectors or high-potential companies. These challenges show the need for a new approach that consolidates funding, sharpens market focus, and demands better results.

Other recommendations proposed in this paper could be enhanced with a more founder-centric, demand-led funding mechanism through a voucher-based model. Instead of government directly subsidising specific accelerators or incubators, companies could apply to receive a voucher – essentially credit that can be redeemed to cover participation in an accredited programme of their choice. This would flip the model to put businesses in the driving seat: companies can shop for the best-fit support using their voucher, creating a demand-led market for incubation and acceleration services and reduce the need for government to pick winners among support programmes.

Similar schemes have been tested in the UK and abroad. For example, the UK’s Growth Vouchers Programme gave thousands of small firms vouchers to spend on business advice. A randomised controlled trial found participating firms saw an 8% increase in turnover in the short term relative to those without vouchers. Across Europe, innovation voucher programmes have been used to connect SMEs with external expertise, which entails lower administrative overheads and less risk of misallocating public funds. In Latvia, a national agency’s voucher-based model supports startups at every stage, from idea to scale. In other words, by empowering companies to choose support services, vouchers can make public funding more agile and responsive, albeit with safeguards needed to ensure additionality and impact.

Such a voucher-based market for entrepreneur support would directly address several issues identified in this paper:

Realign incentives and raise quality. Founders, not grant administrators, decide where to spend their voucher, while providers must deliver relevant, high-impact support to attract participants;

Expand choice and tailoring. Entrepreneurs are no longer confined to whichever local scheme happens to be funded. They can select the incubator or accelerator that best fits their sector, stage, or growth strategy, making support far more tailored to actual needs rather than a one-size-fits-all approach;

Enable smarter regional targeting and specialisation. Policymakers can allocate vouchers in line with local cluster strategies or growth plans, thus channeling resources to where they will catalyse local innovation most effectively;

A voucher system would help avoid the boom-and-bust of short-term programmes. Funding would become an ongoing, demand-driven market rather than a series of temporary projects.

RECOMMENDATION 4:

LAUNCH A VOUCHER-BASED FUNDING MECHANISM

Under this scheme, vouchers would be issued directly to entrepreneurs and would be redeemable with support providers accredited in line with previous recommendations in this paper. This model would realign public funding with market demand and verifiable outcomes while maintaining price discipline and protecting proven support programmes. It could be a route to overcome the inefficiencies of fragmented, grant-led programmes by empowering businesses to choose the support that catalyses their growth.

Administrative setup: We recommend that Innovate UK would pilot this approach in targeted regions or sectors, with a view to scaling it.

To guard against fee inflation, voucher denominations should follow pre-pilot benchmark studies of existing accelerator pricing and be adjusted annually for CPI-X (inflation minus an efficiency target). Innovate UK would publish and annually refresh a transparent price band table. Providers would not be allowed to redeem vouchers above the lowest relevant band unless the company co-pays the difference from private funds.

This demand-driven voucher scheme could drive higher-quality support, streamline administration, and sharpen the strategic focus of innovation funding.

Voucher allocation and eligibility: Vouchers will be competitively awarded via two complementary tracks to maximise impact, equity and cost-effectiveness. Companies would apply for a voucher by outlining their needs and intended accredited accelerator. Each voucher would cover the full cost of programme fees. Eligibility criteria should be clear but broad and prioritise underserved but high-potential companies, for example those at the proof-of-concept stage.

Allocation could be split along two complementary tracks: a cluster-aligned route (where each region or sector has its own voucher slots allocated by local criteria) and a national competitive route (where any qualifying firm competes for open vouchers). Some vouchers or scoring bonuses should be reserved for firms in economically lagging regions or critical technologies. Where oversubscription occurs, a weighted random draw among the top-scoring applicants can be used to avoid grant-writing arms races and ensure smaller companies have a fair chance.

To encourage more aligned public-private co-funding, corporates would be able to buy into the scheme by funding vouchers to investigate a set of requirements or issues within their business or sector.

Accreditation of support providers: A registry of approved accelerators, incubators, and other business support programmes would form the backbone of the voucher marketplace. Providers should meet minimum standards, as outlined earlier in this paper, to ensure quality assurance.

Innovate UK could maintain this registry, conducting due diligence on applicants. Quality review will be led by an Independent Accreditation Council made up of founders, investors, and sector experts, with Innovate UK acting as secretariat. Members will be bound by a strict conflict-of-interest code. Providers must publish a standard price list on the registry and agree to open-book cost audits on request.

Public and private sector providers – from university-affiliated initiatives to private accelerators – could be included as long as they meet the criteria.

Providers would agree to a common set of terms, including transparent pricing for services (since they’ll redeem vouchers for payment) and data-sharing on outcomes for participating firms in line with earlier recommendations in this paper.

The approved provider list should be continuously updated, allowing new entrants that prove their value to join, keeping the market for support open and competitive.

Monitoring and evaluation: Implementing vouchers at scale offers an excellent opportunity for rigorous evaluation of what works. We propose building in an outcome-tracking system from the start. Each voucher redemption could be logged with details of the recipient company and support received. Follow-up data (such as one- and two-year post-support business performance) should be collected to assess additionality. Accreditation will be reviewed each year on the basis of an independent evaluation following international best practice such as, for example the OECD methodology on RCT-type evaluation of entrepreneurship programmes. Providers that fail to show impact would potentially lose their accredited status and with it the right to accept vouchers.

We acknowledge that successful implementation requires further design work, particularly around price benchmarking, independent accreditation governance and evaluation protocols. The voucher scheme should also include safeguards to ensure core funding for proven programmes continues, preventing vouchers from becoming a cover for budget cuts to effective existing support. By embedding appropriate safeguards, the scheme can avoid past pitfalls of cost escalation and ensure a level playing field between university-affiliated and private accelerators.

conclusion

Britain’s accelerator ecosystem is more extensive and active than ever – a testament to the country’s entrepreneurial spirit and investment in startup support. But quantity has outpaced quality and coherence. The proliferation of programmes has introduced fragmentation, variable standards, and inefficiencies that blunt the overall impact.

Several key insights have emerged from our analysis. First, clarity matters: without shared definitions and expectations, accelerators and incubators cannot be effective connectors of talent, ideas, and capital. Establishing common standards and transparency is a way to ensure trust and efficacy in the support offered to founders. When entrepreneurs know what to expect from a gold-standard accelerator and can distinguish it from a basic workshop series, they can make better choices – and the market of support services can evolve through informed competition.

Second, a founder-centric perspective is crucial. The ultimate success of an incubator or accelerator should be measured by the entrepreneurs it empowers, not just the startups it churns out in a given quarter. This long view recognises that building a successful company often involves learning from failures and trying multiple times. Such human capital development is a public good that warrants public support, but it requires patience and smarter metrics to appreciate its value.

Third, consistency and focus should replace short-termism and scattershot approaches. An accelerator that steadily operates and iterates for a decade, for example, can build an enduring community and reputation that multiplies its impact far beyond what any two-year pilot could achieve.

If Britain is serious about harnessing the full potential of its entrepreneurial talent, it must treat accelerators and incubators not as quick fixes, but as long-term infrastructure – worthy of clarity, consistency, and thoughtful design.

acknowledgements

The Entrepreneurs Network would like to thank the following experts for their input and feedback (while noting that contribution does not equal endorsement of points made in the paper).

Steve Aicheler, Enterprise Educators UK

Laura Bennett, Royal Academy of Engineering

Fabio Bianchi, Oxentia

Jonathon Clark, Capital Enterprise

Jamie Clyde, Independent adviser

Chris Fellingham, Kindling Ventures

Tom Forth, The Data City

David Herbada, Zinc

Gareth Jones, TownSq

Neil Marshall, ChangeSchool

Hamish McAlpine, Oxentia

James Phipps, Nesta

[1] Based on the April 2025 data release.

[2] In line with Beauhurst’s definitions: Green status means that an accelerator is accepting applications, or that recent activity has been noticed; Amber status means that an accelerator appears to be active, but not recent activity has been noticed; Red status means that the fund or accelerator appears to be closed or inactive, or has closed for the year in the case of an accelerator.

[3] See Center for Theory of Change, UN Development Group Theory of Change guidance, and the New Philanthropy Capital’s Creating your Theory of Change workbook for practical templates.

For the full version of the report, click here.