By Eamonn Ives (Research Director, The Entrepreneurs Network) and Philip Salter (Founder, The Entrepreneurs Network)

Executive summary

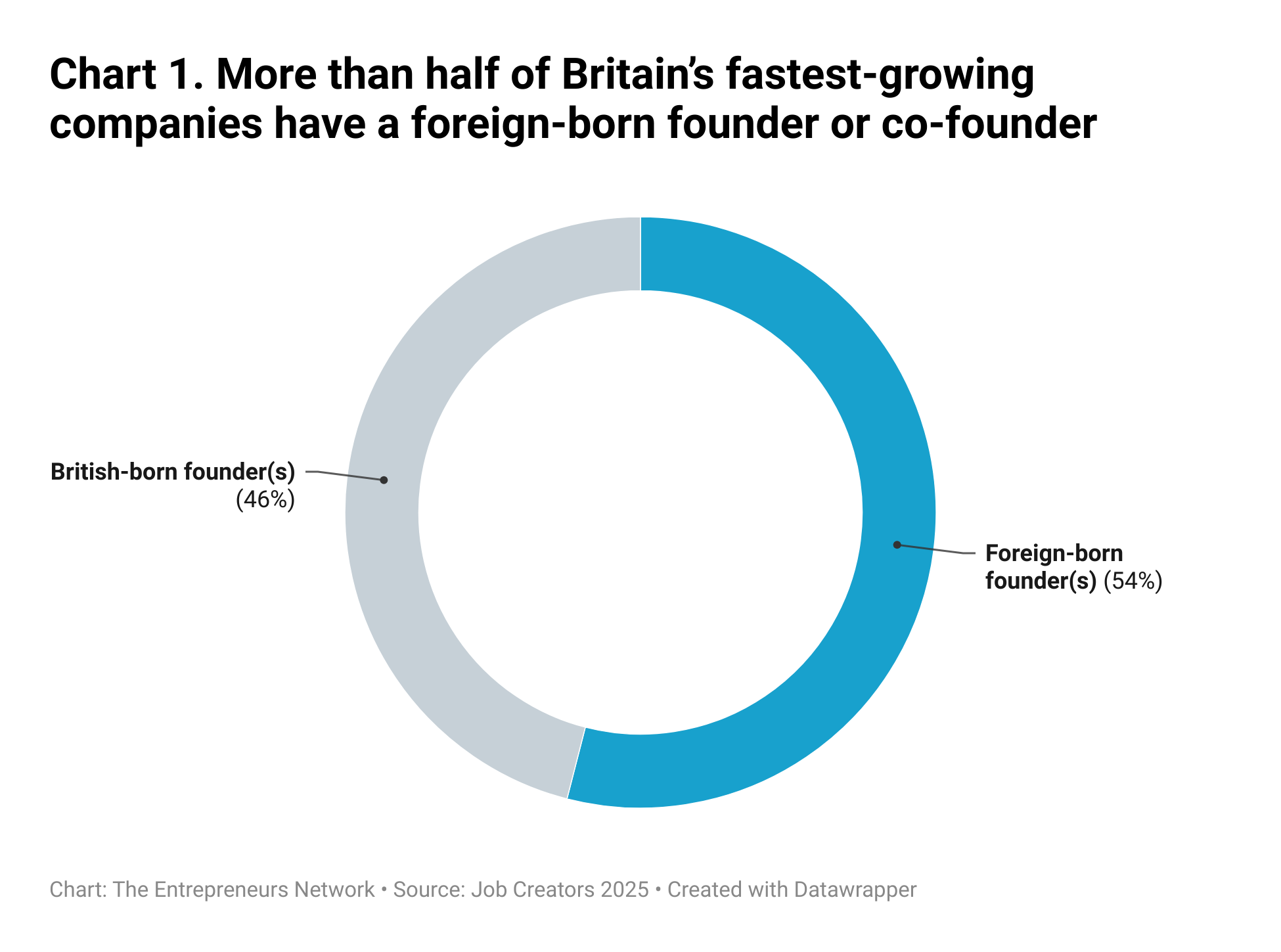

Of the United Kingdom’s 100 fastest-growing companies, 54 have a foreign-born founder or co-founder.

These immigrant founders come from across the world – with France being the most common country of origin, followed by the United States, Belgium, Germany and Italy, and 24 other nations.

Compared to our previous analysis published last year, the proportion of Britain’s fastest-growing companies with a foreign-born founder or co-founder has increased sharply – and is in fact the highest proportion we have ever seen.

We believe that this once again shows the critical contribution that international talent makes to Britain’s entrepreneurial ecosystem. Without their effort and vision, our economy would be less dynamic and competitive, and tax revenues would be smaller.

It also underlines the importance of having an immigration system which enables and encourages high-skilled individuals and those with high potential to come to Britain.

We conclude with five broad policy recommendations to improve Britain’s immigration system for entrepreneurs and those who support them:

1) Protect fast-track settlement for exceptional talent. The Government must preserve accelerated pathways to permanent residence (Indefinite Leave to Remain, or ILR) for high-value visa categories and ensure their families can settle on the same timeline.

2) Reform the Global Talent visa to attract world-class operators. The Government should adjust the criteria of the Global Talent visa and add new sub-categories so that experienced tech operators and ecosystem builders are also welcomed.

3) Make the Innovator Founder visa more functional. The Government must trust the expert endorsers, offer faster processing, and align settlement requirements with startup realities.

4) Design a selective Spinout visa for graduates and academics. The Government should build on its commitment to help more academics at British universities to start companies by designing a selective Spinout visa with strict quality controls and a clear path to settlement.

5) Mitigate financial and administrative barriers for startups. The Government should reduce the cost burdens and cashflow strains that the visa system places on early-stage companies and entrepreneurs.

foreword: Nick Rollason — PARTNER AND Head of Immigration, Kingsley Napley

Entrepreneurial talent is a cornerstone of the UK’s economic vitality and its future growth. Now more than ever, the ability to attract and retain innovative minds from across the globe is a strategic imperative for driving growth and competitiveness.

As evidenced in this report, international founders are not peripheral contributors – they are central to the success of the UK’s startup ecosystem. Their ideas, investment and ambition complement and support homegrown innovation – driving innovation and progress across key sectors.

At a time when the broader immigration policy landscape is being reshaped by external forces, it is vital that the UK Government stays focused on remaining open to global talent that can build businesses that create jobs and provide the revenues that pay for public services. The recommendations set out in this report offer timely and practical proposals for improving and expanding immigration options for founders and strengthening the UK’s position as an attractive destination for entrepreneurial talent. With competition for skills and ideas intensifying, the need for agile and forward-looking reforms like these cannot be overstated.

Kingsley Napley is proud to support this report and wider evidence-based reform that helps to make Britain the best place to start and grow a business in the world.

Introduction

Anyone even remotely familiar with Britain’s entrepreneurial ecosystem will be acutely aware of the significant contribution that immigrants make to it. When we polled entrepreneurs in our network earlier this year, nearly nine in 10 agreed that immigration is important to Britain’s entrepreneurial ecosystem – with 59% describing it as ‘very important’. [1] Whether they’re founding companies, supporting them as employees with scarce skills, or providing startups with capital to grow, individuals who have actively chosen to come to the United Kingdom are a critical ingredient in our leading entrepreneurial ecosystem.

For years, we at The Entrepreneurs Network have sought to put hard data behind the anecdotes we repeatedly hear about the importance of immigration to Britain’s startup economy. [2] Principally through our Job Creators series, we have documented the disproportionate contribution that foreign-born founders make with respect to starting and scaling some of Britain’s fastest-growing businesses.

Beyond that, we have tirelessly advocated for Britain to ensure that its immigration system is fit for purpose – recommending policies that ensure the world’s brightest and best have navigable and accessible pathways to come to the UK and start contributing to our economy. Our findings have been repeated at the highest levels of government, [3] and many of the policy proposals we have recommended have gone from words on a page to law of the land.

With all that being said, it would be wholly naive to ignore the political context we currently find ourselves in. Though overall numbers of people coming into the country are steadily falling, limiting immigration remains a top priority for many voters in the UK. [4] Mainstream parties are pledging to enact stricter policies to further reduce immigration, while once fringe ones have shot to prominence precisely because of their willingness to restrict who can come into the UK.

In May of this year, the Government set out its plan to “restore confidence in the immigration system” by publishing its Immigration White Paper. [5] Among the main policies it put forward were toughening up language requirements, shortening the duration of Graduate work visas, lengthening the time required to qualify for Indefinite Leave to Remain and citizenship, making the Immigration Skills Charge more expensive, and increasing the stringency of who qualifies for a Skilled Worker visa.

At the same time, the Immigration White Paper recognised that “the race to attract the most desirable talent is fierce” and detailed a handful of ways the Government would seek to make it easier for “the very highly skilled” to come to Britain. [6] Promises were made to streamline visa bureaucracy for scientists, to improve the Innovator Founder visa, and to expand the number of universities whose graduates would be eligible to qualify for the High Potential Individual visa. [7]

While there is much of the Immigration White Paper we do not endorse – and while there are parts we do – it should be understood that the Government is treading an extremely narrow path. Politics dictates that the Government needs to appear tough on low skilled migration if it is to stand a chance of staying in power. In doing so, however, it cannot afford to screen out high skilled individuals. Few in society want an immigration system that prevents top entrepreneurs, investors, engineers or scientists from coming here to help contribute to the economy. As much as concerns over immigration have risen up the polls, the economy remains a close second, and, come the time of the next election, will be a critical factor determining how people vote. [8]

Yet, as we shall turn to later, aspects of the Immigration White Paper will almost certainly filter out precisely the sorts of people we desperately need more of in Britain today. Either proposed changes will block existing pathways entirely, or simply just make going through the process less attractive on the margin. Talented individuals will decide that other countries may be more enticing destinations to move to. Hard policy will of course be the biggest determinant here, but it should also be recognised how much rhetoric matters too. In our regular conversations with foreign-born members of Britain’s entrepreneurial ecosystem, too many people tell us they no longer feel welcome in our country – and are exploring options to relocate. It must be remembered that entrepreneurs are not just economic units, but real people – who see, hear and feel the changing mood of the country every day. We believe Britain remains an attractive country for immigrants to come to and build in, but we forget at our own peril that entrepreneurial talent is highly sensitive to change and agile by nature.

Thus, while we sympathise with the Government’s current predicament, we urge it to proceed with utmost care. Where policies are introduced to reduce immigration, they must be targeted and carry a clear justification. An all too common theme when it comes to reforming Britain’s immigration system is to enact sweeping changes that inevitably ensnare precisely the sorts of people we should be grateful to have expressed an interest in moving to our country. One-size-fits-all policies seldom work well for anyone. Invariably, they simply deny both international talent the chance to flourish and the British population the opportunity to benefit from their success – whether through new jobs created, tax receipts generated, investment made, or innovations supplied.

As the Government begins to implement aspects of its Immigration White Paper, we implore it to weigh the needs of Britain’s existing and potential startups seriously. As we set out later in this paper, we believe there are a handful of ways it can ensure that it achieves its policy intentions while ensuring damage to our lucrative entrepreneurial ecosystem is limited.

Key findings

Our latest analysis reveals that 54 of the UK’s 100 fastest-growing companies have a foreign-born founder or co-founder. This represents the highest proportion we have seen since we first carried out this research in 2019.

Among the 219 founders and co-founders behind this year’s companies, 91 – or 42% – were born overseas. These statistics underscore the significant contribution that immigrants make to the UK’s entrepreneurial landscape. Of the 54 immigrant-founded or co-founded companies, 24 were established entirely by foreign-born teams, while the other 30 were joint efforts between British-born and immigrant co-founders – emphasising how immigrant founders often come to the country and complement, rather than crowd out, British-born entrepreneurs.

It is surprisingly difficult to calculate immigrants as a proportion of the total population, at least in a timely fashion. Nevertheless, Migration Observatory analysis of the latest census and Annual Population Survey data shows that the foreign-born population of the United Kingdom stood at around 16% in 2023. [9] In the years since, net immigration will have pushed this figure higher, as it far outweighs what is referred to as ‘natural population change’ – the difference between non-immigrant births and deaths. [10] More recent estimates suggest the immigrant population of just England and Wales could be closer to 18%. [11]

The foreign-born founders in this year’s sample hail from 29 unique countries across six continents – a rise in the spread from last year’s 22. France was the most common birthplace for founders in our sample, with 12 being born there. That was followed by the United States, Belgium, Germany and Italy with seven founders, Australia and Denmark with six, Ireland with five, India and Spain with four, Ukraine with three, Canada, Estonia, Greece, Singapore and Sweden with two, and one each from Austria, Bulgaria, China, Iran, Israel, Japan, Kazakhstan, the Netherlands, Romania, Somalia, South Africa, Syria, and Venezuela.

Once again, these data are proof that foreign-born founders make an integral and outsized contribution to Britain’s entrepreneurial scene – starting and growing innovative companies which advance the economy forwards. Our findings only serve to emphasise the importance of crafting an immigration system, and overall environment, that is navigable for attractive to high-skilled immigrants. As we will turn to in the next section, there are a number of ways in which the Government can thread the needle of retaining control of the immigration system while still enabling international talent to easily move to Britain and begin building incredible companies here rather than elsewhere.

case study: Teru adachi — founder, aprio technologies

By the age of six, Teru Adachi was already writing software. That childhood fascination with technology would eventually lead him to relocate across the world, from Japan to London, where, as the sole Founder of APRIO TECHNOLOGIES, he is now developing a cyber risk management platform that helps companies to manage cyber threats and make better-informed decisions about their operations.

Teru describes how the idea for his company arose from confronting a persistent problem he witnessed during his career in cybersecurity: the lack of a common language between technical cybersecurity and business strategy. “Over decades in the industry, I repeatedly saw how traditional risk assessments were static snapshots that failed to engage leadership or keep pace with evolving threats,” Teru says, before adding: “One pivotal moment was realising that supply chain cyber attacks – some of the most destructive – often exploited unseen vulnerabilities in distant third parties. Yet, companies had no way to monitor those risks holistically.”

Reflecting on his journey to being based in the UK, Teru notes how it was an easy, and deliberate, decision: “First and foremost, the UK offers a vibrant ecosystem for technology and startups. London is one of the world’s leading financial centres, which means access to capital and a concentration of potential clients and partners – especially in sectors like finance and insurance that are crucial for our cyber risk platform. Being in the UK has given us proximity to global investors and the credibility of a London-headquartered company, which is valued by customers – even in other markets like Japan. In fact, the UK’s reputation for high cybersecurity standards and innovation has been a strong asset when approaching clients and partners internationally.”

Teru also praises the density of talent that London offers: “The presence of world-class universities and talent was another big draw. Our company collaborates with researchers from institutions such as UCL, and being located in the UK makes it easier to tap into that pool of expertise and cutting-edge research. Culturally, the UK is also very welcoming to entrepreneurs from abroad. I’ve found the business community in London to be diverse and open-minded, with a healthy respect for innovation and new ideas. The government’s support for tech entrepreneurs (for example, through programmes like the Global Talent visa I received) also signalled to me that the UK is serious about attracting international talent. All these factors – from capital and talent to language and a supportive culture – made the UK an ideal choice for building and growing our business.”

One aspect of the immigration system Teru is less positive about, however, is how he feels it is geared towards bigger companies. As he puts it: “Right now, even if we find a brilliant candidate overseas, the procedures for sponsoring a visa – from obtaining a sponsor licence to meeting stringent salary thresholds and compliance rules – are onerous for a small firm. These requirements were designed with larger corporations in mind, and they can inadvertently hinder startups that need to bring in specialist talent quickly to remain competitive.”

case study: Dimitri Masin – Co-Founder, Gradient Labs

Dimitri Masin remembers coming to Germany from his native Kazakhstan in the late 1990s. “Arriving as a small kid and knowing no German was challenging,” Dimitri tells us. It was only after proving himself in mathematics Olympiads that his headteacher took a chance on him – allowing Dimitri entry to a gymnasium, Germany’s most advanced secondary school type. “That small break shaped everything that followed,” Dimitri says.

Today, Dimitri is one third of Gradient Labs’ founding team. An AI platform purpose-built for financial services, Gradient Labs seeks to end a frustration that Dimitri and his co-founders witnessed repeatedly while working together at Monzo Bank. Whether overseeing fraud detection or customer operations, they saw how automation tools were either too rigid to handle nuanced customer interactions, or too risky for compliance-heavy financial environments. As Dimitri explains: “We’re motivated by the belief that financial services can deliver exceptional quality support at scale – and that AI, if designed properly, can make this a reality.”

After studying at the University of Münster, Dimitri began his career at Google’s European headquarters in Dublin before moving to London with the company. As he puts it: “London was already starting to feel like the centre of gravity for financial technology. Banks, regulators, investors, startups – all clustered together in one city. You could feel the energy of it.”

Dimitri sees the immigrant experience as fundamental to his entrepreneurial journey. He notes how it “forces you to adapt quickly, to push through language barriers, to prove yourself in places where nobody really knows you. Those early years taught me resilience and the willingness to take risks. Both turned out to be essential as an entrepreneur. Living in different systems and cultures has given me a broader perspective. You start to see opportunities, and problems too, from more than one angle. That perspective has been invaluable as we’ve built a company meant to work not just in Britain, but across international financial institutions.”

That international outlook extends to how Gradient Labs approaches talent. “In today’s AI-driven world, there’s a global war for talent. The best people can come from anywhere, and countries that restrict access will struggle to stay competitive. AI specialists are in short supply, not just in the UK, but worldwide,” Dimitri says. He also reflects on the hurdles Gradient Labs has faced when bringing in international talent: “The biggest frustration was the time it took to bring someone in quickly, especially since we had no way to expedite the process. For a startup like Gradient Labs, speed is one of our advantages, and every day they’re not here, we lose momentum. We’d be happy to pay for a faster option if one were available!”

Dimitri’s main ask when it comes to improving the immigration system is to accelerate everything: “What would help is a faster, simpler visa pathway tailored to growth companies. It would cut out a lot of unnecessary friction and, in the long run, help Britain stay competitive as a global hub for technology and financial services.”

Case study: Kevin Lester – Co-Founder, Validus

The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 exposed fundamental weaknesses in how financial institutions managed risk. But for Kevin Lester, who was at the time working at a brokerage firm in London, it revealed something more specific – standard risk management and hedging techniques simply didn’t work for private capital, and there was no technology built to meet the specific needs of this growing market segment.

Kevin and his co-founder decided to address that gap, founding Validus Risk Management in 2010 to provide financial risk advisory and purpose-built technology for the private capital industry.

For Kevin, the path to the United Kingdom began in Canada, where he grew up and attended university before spending seven years working in Switzerland’s financial services sector. When he moved to the UK in 2007, London’s position as a leading financial centre made it the logical next step for someone in the industry, but Kevin also cites the English language and London’s broader cultural appeal as reasons which reinforced his decision to relocate.

Reflecting on his experience as a foreign-born founder in Britain, Kevin is emphatic about how positive it has been. “I think it would be difficult to imagine having the same success elsewhere due to London’s unique position as both a leading financial center and as a tech hub, which is crucial for hiring the talent we need,” he notes.

London has proven an effective launchpad for Validus to grow internationally, too. Kevin notes how they have successfully expanded into Europe, leveraging proximity and relationships there, and how they have also begun to enter the US market, after establishing a subsidiary firm.

Kevin believes the immigrant experience has been pivotal to his own entrepreneurial journey. “Being an entrepreneur requires resilience, and I feel that setting up shop abroad tests how capable you are to push through in a whole new context,” he explains. The perspective has shaped not just his own approach but also his hiring philosophy – Kevin actively looks for people who have lived abroad, viewing international experience as a meaningful indicator of adaptability and determination. Validus’ workforce reflects that conviction, with approximately half of the company’s employees coming from overseas.

While navigating the immigration system hasn’t presented major obstacles to date, Kevin notes that it’s becoming more difficult. His recommendation to the Government is succinct: “Don’t make it more difficult!”

Case study: Jing Ouyang – Co-Founder, Patchwork

While working as locum doctors in NHS hospitals, Jing Ouyang and his co-founder Anas Nader knew the frustrating inefficiency of booking shifts all too well. As they saw things, the process was unnecessarily complicated and meant hospitals regularly defaulted to using expensive external agencies to fill vacancies. But Jing and Anas also believed in the power of technology to provide a better way forward – which would enable hospitals to utilise their existing clinical staff – and together founded Patchwork to solve exactly that problem.

Having first met at Imperial College London, Jing and Anas learnt they each had a passion for medical innovation and technology, and collaborated on student projects together. Jing admits none of these went anywhere in particular, but when they reconvened years after graduation to launch Patchwork, they could do so seamlessly.

Jing’s journey to Britain began when he was aged just four years old. Originally born in China, he moved to the UK when his parents pursued academic opportunities in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution. He describes the transition as “relatively straightforward,” with his parents applying for visas early and successfully navigating the process.

Nevertheless, arriving as a young child in an entirely new country left a lasting mark on Jing: “You are an outsider so you develop a completely different mindset, and learn to be adaptable,” he reflects.

Jing is emphatic about the connection between his background and his drive to build a company. Being foreign-born but raised in the UK created a unique combination – with Jing noting: “I think the combination of being foreign-born but raised in the UK does make you develop a different mindset, and I think it goes some way to explaining why so many founders are immigrants. It’s this unique combination upbringing that forges the characteristics needed to pursue a startup.”

For Patchwork itself, access to international talent has been crucial for scaling, particularly when hiring software engineers. While Jing says the immigration system hasn’t been a huge blocker to growth – though he laments how costly and time-consuming it can be – having ready access to a wide talent pool is indispensable. Ultimately, Jing says that anything which can make it easier for high-skilled workers to get work visas would be welcome.

Policy Proposals

As noted above, the Government has been implementing parts of its Immigration White Paper since it was unveiled earlier this year. Working with leading founders, startup ecosystem builders and immigration lawyers, we believe there are a handful of small but significant changes the Government could still make to ensure that Britain remains an attractive destination for international talent to build, without materially undermining the Government’s overall ambition to limit numbers of immigrants coming to the UK.

Recommendation 1: Protect fast-track settlement for exceptional talent

To keep Britain attractive to top global talent, the Government must preserve accelerated pathways to permanent residence (Indefinite Leave to Remain, or ILR) for high-value visa categories and ensure their families can settle on the same timeline.

The Government should:

Maintain accelerated ILR pathways for high-value visa categories: Visa categories such as Global Talent, Innovator Founder, and any new high-skill visas should continue to provide expedited routes towards ILR. This means explicitly exempting these categories from the proposed 10-year standard settlement track outlined in the Immigration White Paper’s “earned settlement” model for ordinary work visas. These selective pathways target individuals who create jobs and attract capital; forcing them onto a 10-year timeline would contradict their core purpose and has already alarmed tech founders and investors who rely on fast certainty about their status.

Align dependent settlement timelines with main applicants: Spouses and children of talent-visa holders should be able to settle just as quickly as the main applicant, rather than facing drawn-out processes. When dependents encounter longer and more expensive routes to ILR it strongly deters family relocation. Matching family settlement timelines removes this barrier. Founders and investors often evaluate immigration security for the whole family before choosing the UK – if a founder’s family faces uncertainty or a decade-long wait, it can be a deal-breaker for bringing high-value ventures to Britain.

Recommendation 2: Reform the Global Talent visa to attract world-class operators

To broaden the appeal of the Global Talent visa, the Government should adjust the criteria and add new sub-categories so that experienced tech operators and ecosystem builders are also welcomed.

The Government should:

Recalibrate the endorsement criteria: Overly restrictive criteria are currently causing even highly qualified candidates to be rejected. Right now the bar is so high that accomplished individuals (product managers, growth leads, go-to-market executives, CTOs, and so on) and even repeat founders with solid track records are being turned away. The heavy emphasis on having worked in or founded a strictly defined “product-led digital tech company” is too narrow and excludes talent from adjacent innovative sectors. The endorsement standards should focus on real-world impact and contributions rather than rigid checkboxes. In practice, this means broadening the definition of eligible “tech” experience (encompassing fintech, regtech, biotech, and other technology-enabled fields) and valuing significant achievements in a role even if they were within a larger firm or a non-traditional startup model.

Create an ‘Ecosystem Builder’ pathway: We should establish a dedicated Global Talent sub-route for investors, mentors, and accelerator leaders who actively support early-stage companies. This would recognise those whose experience, networks, and capital strengthen the UK’s startup ecosystem, even if they are not founders themselves. Founders consistently cite the strength of the UK’s investor and mentor network as a key reason to grow their companies locally. Yet under current rules, a successful American investor-mentor who wants to help British startups grow cannot easily get a visa unless they take a traditional job with sponsorship at a large firm – an ill-fitting option that deters these contributors. By welcoming these high-impact individuals who have already achieved success and are motivated by helping new companies grow, the UK would strengthen the support structure available to all founders and signal that it values the entire innovation ecosystem.

Pilot a C-Suite Talent Visa: A targeted visa should be created to attract top-tier executives from global companies (Fortune 500 corporations or internationally successful scaleups) to come and help scale UK-based companies. The focus should be on seasoned professionals in roles that British unicorn-aspiring firms often struggle to fill domestically – such as heads of global sales, chief operating officers, experienced compliance officers in fintech, or other commercialisation experts. This visa should offer broad work freedom (not tied to a single employer sponsor) to make it attractive and to enable entrepreneurial individuals to be flexible while on it. By piloting this C-suite talent route, the UK can infuse its high-growth companies with proven leadership experience, which in turn helps home-grown startups scale up into globally competitive firms without having to leave the UK.

Recommendation 3: Make the Innovator Founder visa more functional

The Innovator Founder route should enable entrepreneurship, but in practice it has become mired in red tape and unrealistic criteria. To fix this, the Government must trust the expert endorsers, offer faster processing, and align settlement requirements with startup realities.

The Government should:

Stop second-guessing endorsements: Home Office caseworkers should not re-evaluate business viability after an endorsing body has approved an Innovator Founder application. Currently, after founders secure endorsement from authorised experts, caseworkers often double-check the business concept’s merits as if they were venture capitalists – asking Dragon’s Den-style questions and sometimes delaying decisions for months. These officers are typically not equipped to make sophisticated commercial judgments, and this second-guessing undermines the very point of having specialist endorsing bodies. It also disrupts founders, who may need to travel on short notice for investor meetings or customer deals. Once an endorsing body has vetted and approved a business idea, the caseworker’s role should be limited to standard administrative checks (fraud, identity, security, etc.), not re-litigating whether the business is good.

Introduce premium processing for founders: A paid 48-hour or five-working-day decision service (even at an additional fee) for Innovator Founder visa decisions and travel documents should be introduced, similar to expedited options in other visa categories. Founders often must travel with little notice to raise capital, attend conferences or meet customers. Under the current system, there is no reliable way to expedite an Innovator Founder application or get a rapid travel endorsement, which can lead to missed opportunities. A premium processing service would ensure that entrepreneurs can respond quickly to their business’ needs.

Reform settlement criteria to match startup reality: The requirements for Innovator Founders to qualify for ILR should reflect genuine startup progress rather than arbitrary early-stage revenue or headcount thresholds. Currently, the accelerated settlement criteria demand that a startup founded on this visa show significant traction – such as employing a certain number of people or hitting certain revenue levels – within just a few years. In practice, even very promising startups often take more time (and multiple funding rounds) to reach those metrics, meaning most cannot meet the ILR test and are forced to either extend their visa or switch to a sponsored Skilled Worker visa at their own company. The policy should be rewritten to evaluate success through more reasonable and achievable milestones.

Recommendation 4: Design a selective Spinout visa for graduates and academics

Building on the Government’s commitment to help more academics at British universities to start companies, a selective Spinout visa should be created with strict quality controls and a clear path to settlement. This new route would encourage top university talent to grow their ventures in the UK.

The Government should:

Target proven incubators and spinout programmes: The new visa should focus on graduates of high-performing incubators, accelerators, and university commercialisation programmes, rather than allowing any university to sponsor would-be entrepreneurs (a mistake of the old Startup visa scheme). Endorsement powers should be limited to the most credible organisations who are helping to churn out startups.

Count time spent on a Spinout visa towards settlement: Years spent on the Spinout visa should count towards ILR. Early-stage founder visas in the past did not count towards ILR, which discouraged uptake and undermined the whole purpose of these routes.

Implement real oversight and support via endorsing bodies: Endorsing institutions (incubators, accelerators, or university programmes) should play an active role in monitoring and supporting the visa holders’ progress, rather than just signing off paperwork.

Recommendation 5: Mitigate financial and administrative barriers for startups

Finally, the Government should reduce the cost burdens and cashflow strains that the visa system places on early-stage companies and entrepreneurs. Even when visa routes are favourable on paper, prohibitively high fees and inflexible payments can make it harder for startups in practice from hiring internationally, as well as discouraging founders from choosing the UK to begin with.

The Government should:

Freeze or reduce visa costs for founders and small companies: Further increases to immigration fees for those in founder and high-talent categories, as well as for small high-growth companies, should be avoided and ideally reduced. This includes visa application fees, the Immigration Skills Charge, and the Immigration Health Surcharge.

Allow staggered payment of immigration fees: Approved startups and entrepreneurs should have the option to pay required immigration costs in instalments over the duration of a visa, rather than all upfront.

Overall, this package of recommendations aims to keep the UK competitive for founders and highly skilled talent while still maintaining the integrity of immigration system. The focus is on targeted improvements and assurances for high-value migrants – those who create jobs, innovate and attract investment – rather than broad-brush immigration liberalisation.

It’s also important to recognise that beyond the letter of policy, the rhetoric and signals a country sends about immigration have a huge impact. Negative messaging, constant rule changes and uncertainty about long-term prospects make talented people feel unwelcome. In the global competition for talent, deterrence can occur even when pathways technically exist – if people believe that after investing years in the UK they might not be allowed to settle or that the rules might change arbitrarily, many will choose more welcoming countries that offer greater certainty.

These recommendations would facilitate more high-value talent to choose Britain, while also sending a positive message that the UK genuinely wants and values the sort of exceptional individuals showcased in this report, and will provide a stable, attractive environment for them and their families.

Conclusion

Once again, our analysis has highlighted the disproportionate contribution that foreign-born founders make to Britain’s economy. In fact, this year’s analysis stands out as the most compelling evidence we have ever assembled since starting our Job Creators research series back in 2019. For the first time on record, we can say that more than half of Britain’s fastest-growing companies owe their success to someone who actively chose to come to the United Kingdom to build their business.

We should be honored that so many amazing individuals decided to choose Britain over multiple other countries that many plausibly could have. Of course, there are plenty of different reasons why they would have selected the UK as their preferred destination – whether it was access to capital from our strong investment scene, access to talent supplied by our world-class universities, or to benefit from light-touch business regulation and our robust rule of law. The fact that there were pathways for them to come here in the first place, however, applies to them all.

What our analysis cannot show is the fraction of the foreign-born founders in this year’s sample who may have been prevented from moving to the UK based on new immigration rules, or ones that are currently being considered. Nor can it tell us how many might have opted to move elsewhere if they knew the political context they would now be facing, even if they would qualify for a visa and had the means to get one.

Governments cannot know a priori which entrepreneurs or innovators coming to the country will end up directly or indirectly building some of our most successful companies. But with the right policies in place, we can increase the likelihood that those who do immigrate here will positively contribute to our startup economy. In this paper, we set out just three proposals the current Government could adopt to do exactly that – keeping Britain open for business while allowing the Government to maintain a robust stance on immigration overall.

Partners and methodology

Kingsley Napley LLP is a leading UK based independent law firm providing expertise for our clients’ business and private lives when it matters most. We advise in the following areas: corporate and commercial, criminal, dispute resolution, employment, family & divorce, immigration, medical negligence & personal injury, private client, public law, restructuring & insolvency, real estate & construction, and regulatory law. For more information about the firm visit kingsleynapley.co.uk.

This research uses data from Beauhurst. With their data, we established a list of the 100 companies which had experienced the greatest growth in reaching a valuation observed between June 2024 and the end of May 2025. The list excludes companies that had raised in total less than £25,000, had a pre-money valuation of less than £1 million or that gave away a majority stake in their pre-June 2023 equity transaction

From this list, we established who the founders of those companies were, and their respective nationalities. We cross referenced this with further research and analysis of Companies House data, and finally reached out directly to the companies to verify the information was accurate.

While we recognise that any metric designed to identify the UK’s fastest-growing companies will have drawbacks, we nonetheless believe the Top 100 is a useful snapshot of the UK’s most innovative and high-growth startups and scaleups.

For more information about Beauhurst, please contact Henry Whorwood, Head of Research & Consultancy at henry.whorwood@beauhurst.com.

Beauhurst is the ultimate private company data platform. Beauhurst sources, collates and analyses data from thousands of locations to create the ultimate private UK company database. Whether you’re interested in early-stage startups or established companies, Beauhurst has you covered. Beauhurst's platform is trusted by thousands of business professionals to help them find, research and monitor the UK’s business landscape. For more information and a free demonstration, visit beauhurst.com.

ENDnotes

[1] The Entrepreneurs Network (2025). Entrepreneurs Survey.

[2] The Entrepreneurs Network (2025). Immigrant founders.

[3] HM Treasury (2021). Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021 Speech.

[4] YouGov (2025). The most important issues facing the country.

[5] Home Office (2025). Restoring control over the immigration system.

[6] Ibid.

[7] An expansion of the High Potential Individual visa recently came into force. Home Office (2025). Explanatory memorandum to the statement of changes to the Immigration Rules: HC 1333, 14 October 2025.

[8] YouGov (2025). The most important issues facing the country.

[9] Migration Observatory (2024). Migrants in the UK: An Overview.

[10] BBC (2025). Year to 2024 sees UK record second largest population growth in 75 years.

[11] House of Commons Library (2025). Migration statistics.